Tragedies occur on all levels in history. Some are catastrophic, involving thousands upon thousands of victims and move the needle measuring the Arc of Progress backwards. Some, though, are those individual ones where an individual’s passing seems so unfair, and that what he or she could have offered us, magnificent examples of man’s potential, are never to be. That comment suffers the absence of describing the absence felt by those closest to the departed individual. Their lives were altered beyond recompense. For us travelers in the future, having learned of those earlier exploits and the nuggets produced from the minds and thoughts of artists, depending on our fullest understanding of “the story” around the individual, our own pain is commensurate to the immediate pain felt by close associates of him who departed this world. The more one learns of the time, perhaps the closer we can share empathic feelings with those who suffered in the moment.

Artists are special in relaying empathic messages. They communicate through metaphor and reimagining the world in a way that offers a singular understanding that allows the rest of us to comprehend beyond the surface, or through the offering of an altered vision that clashes with pablum, propaganda or political biases. Such was the gift of Wilfred Owen.

If you have spent any time studying the Great War, you learn that it was a mistake on so many levels. Not least of which was the ineptitude of the leaders who misunderstood the nature of war as the 20th century began and wished to prosecute a war that was now no longer possible. These leaders asked their soldiers to march towards weapons that could kill at a greater distance, with more force and explosive power and with a rapidity that was truly destructive for all that the hale of bullets met in their paths. Add to that the use of gas and other chemicals, aerial engagement between planes and between the planes and those on the ground. To be a simple soldier required more than perhaps it has ever expected of a human mind and perhaps has not been matched since.

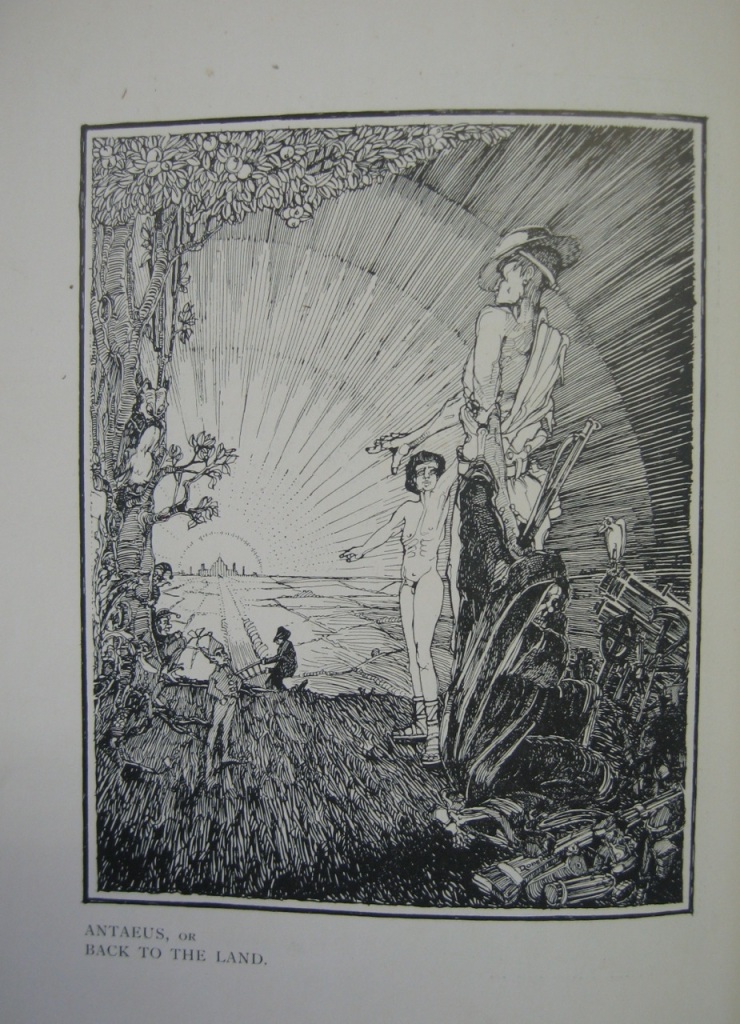

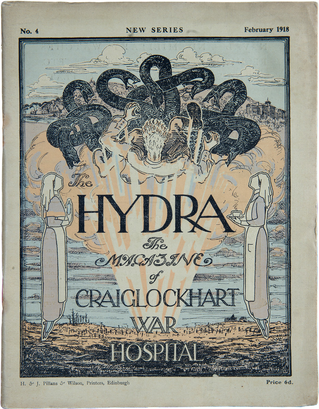

In the midst of this carnage, art took note. Great minds assessed and judged the mistakes, caught the Zeitgeist and measured how fruitless battles had become. Among the greatest was a fledgling poet who had gained his voice through the tragedy of the war, plus a chance meeting while on a rehabilitation stay in Scotland near the end of the war. After suffering injuries and mental trauma from munitions attacks, Owen was sent for the “Talking Cure” at the Craiglockhart Hospital in Edinburgh, Scotland. There the new psychological treatment developed by Sigmund Freud was utilized. It was also here that Owen met Siegfried Sassoon.

Sassoon was already a giant and Owen felt and exhibited this sentiment upon meeting him. At that point Owen was editing the hospital magazine, called the Hydra. In it poems, thoughts and observations about life and the war were offered by the patients. Owen was attempting the art of poetry to incapsulate his nightmares in words. Sassoon would discuss possibilities with Owen and shape his craft through the process. During the day, the doctors would address the pain, at night the war’s impact would reimagine the pain and visions of the dead for yet another time.

When the war broke out, Owen had been in Bordeaux teaching at a school. He was comfortably away from it all and reading about its initial movements from the safety of a summer garden. At that point the British had no draft, only a volunteer army. The longer the war dragged on—it was thought it would only last six weeks or so, and surely be over by Christmas—Owen felt the need to enlist, to prove himself. To quote him and his sentiments about his reasons for seeking honor on the battlefield, it was not “to save my honor before inquisitive grandchildren fifty years hence. But I now do most intensely want to fight.” At the beginning of the war, there was some concept in the public mind that one had to stand up for his country and put his life in danger to accomplish and serve the country’s goals. How he would learn to question these thoughts. He would return to fight in the end, knowing its futility. But, his love of his fellow soldiers was his complete commitment.

To quote Philip Burton Morris, in his article about the poet, ‘Owen was stunned by the vast, pitiless volume of the shells, which he reported back to his family with the visceral precision of an experienced soldier. “It was not a succession of explosions or a continuous roar,” he wrote. “It was not a noise; it was a symphony. And it did not move. It hung over us. It seemed as though the air were full of a vast and agonized passion, bursting now with groans and sighs, now into shrill screaming and pitiful whimpering, shuddering beneath terrible blows, torn by unearthly whips, vibrating with the solemn pulses of enormous wings.” Again from the Morris article, ‘On January 12, 1917, Owen led his battalion up to the Bertrancourt line near Amiens. German forces began to shell them heavily, driving Owen and a section of his soldiers into a damaged hut for cover. The German fire persisted without letup—“The Germans knew we were staying there and decided we shouldn’t,” Owen reported mordantly—and the poet shared space with the ruined body of a dead soldier, petrified, shivering, and unable to escape. “Those fifty hours,” he confessed in a letter to his family, “were the agony of my happy life.” On April 14, 1917, the regiment took part in an offensive at St. Quentin. Moving to support the French left, Owen’s troops had to cross the exposed crest of a hill under heavy shell fire. Owen described the attack. “The sensations of going over the top are about as exhilarating as those dreams of falling over a precipice, when you see the rocks at the bottom surging up at you,” he wrote. “I woke up without being squashed. Some didn’t. Then we were caught in a tornado of shells. The various waves were all broken up and we carried on like a crowd moving off a cricket field. When I looked back and saw the ground all crawling and wormy with wounded bodies, I felt no horror at all but only an immense exultation at having got through the barrage.” In late 1918, after returning briefly to England to recover from a wound and soon to be back in France he recounted to his mother about the earlier battle: “I lost all my earthly faculties, and fought like an angel. I came out in order to help these boys—directly by leading them as well as an officer can; indirectly, by watching their sufferings that I may speak of them as well as a pleader can.” The poet had already proven he could plead their sufferings. The officer now needed to lead his men as well. He did. He was awarded the Military Cross, with the citation reading “On the Company Commander becoming a casualty, he assumed command and showed fine leadership and resisted a heavy counterattack. He personally manipulated a captured enemy machine gun in an isolated position and inflicted considerable losses on the enemy. Throughout he behaved most gallantly.” Owen had proven himself finally, unmistakably to be a soldier.’

Critical to Owen’s writing of poetry is his meeting with Sassoon, and this relationship also flavored Owen’s objections to the war. Even so, both men go back to France, one after openly writing against the war as a famous and respected soldier/poet and the other accepting his treatments and then returning to the Front with a fatalistic attitude towards his own survival. It is with this fatalism that Owen approaches his last year in the war and when he was awarded the Military Cross. Both men’s poems about war are famous; Owens are available here. Dulce Et Decorum Est is read by Michael Stuhlbarg.

My most recent tugging on my anger and anguish at our loss of Owen to the war arrived this week upon a visit to Ripon Cathedral. It is a stunning example as it elicited the thoughts of Owen being virtually in the same spot and location I was then occupying. He spent hours in the calm atmosphere of the Cathedral, which was only a ten minute walk from the flat he had rented while convalescing here in 1918. There is a chapel dedicated to him in the corner to your left as you enter the church. We had just heard an Evensong delivery by a choir from the Netherlands and were much in the mood of contemplation. Earlier visits to the church allowed connections to Lewis Carroll, who gained inspiration from the Cathedral and Ripon, as well as Turner, who painted it. My need to write a tribute to this calm, kind man who only made it to his 25th birthday, which was celebrated in Ripon. Five years’ ago the cathedral commemorated his birthday with poetry readings. Such a tragic loss.

Sassoon, who survived the war and died in 1967, would later write, “W’s death was an unhealed wound, & the ache of it has been with me ever since. I wanted him back—not his poems.” In admittedly the tiniest of ways, I wish to feel that pain for the world’s loss.